In the annals of human history, few civilizations have captured the imagination and evoked such a profound sense of dread as the Aztecs. Known for their awe-inspiring architectural feats, their sophisticated astronomical knowledge, and their unparalleled military prowess, the Aztecs also held a deeply unsettling secret – their ritualized practice of cannibalism.

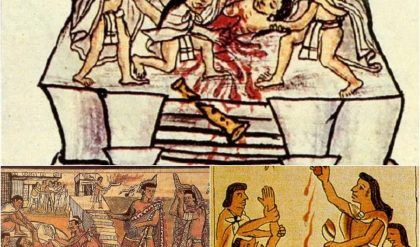

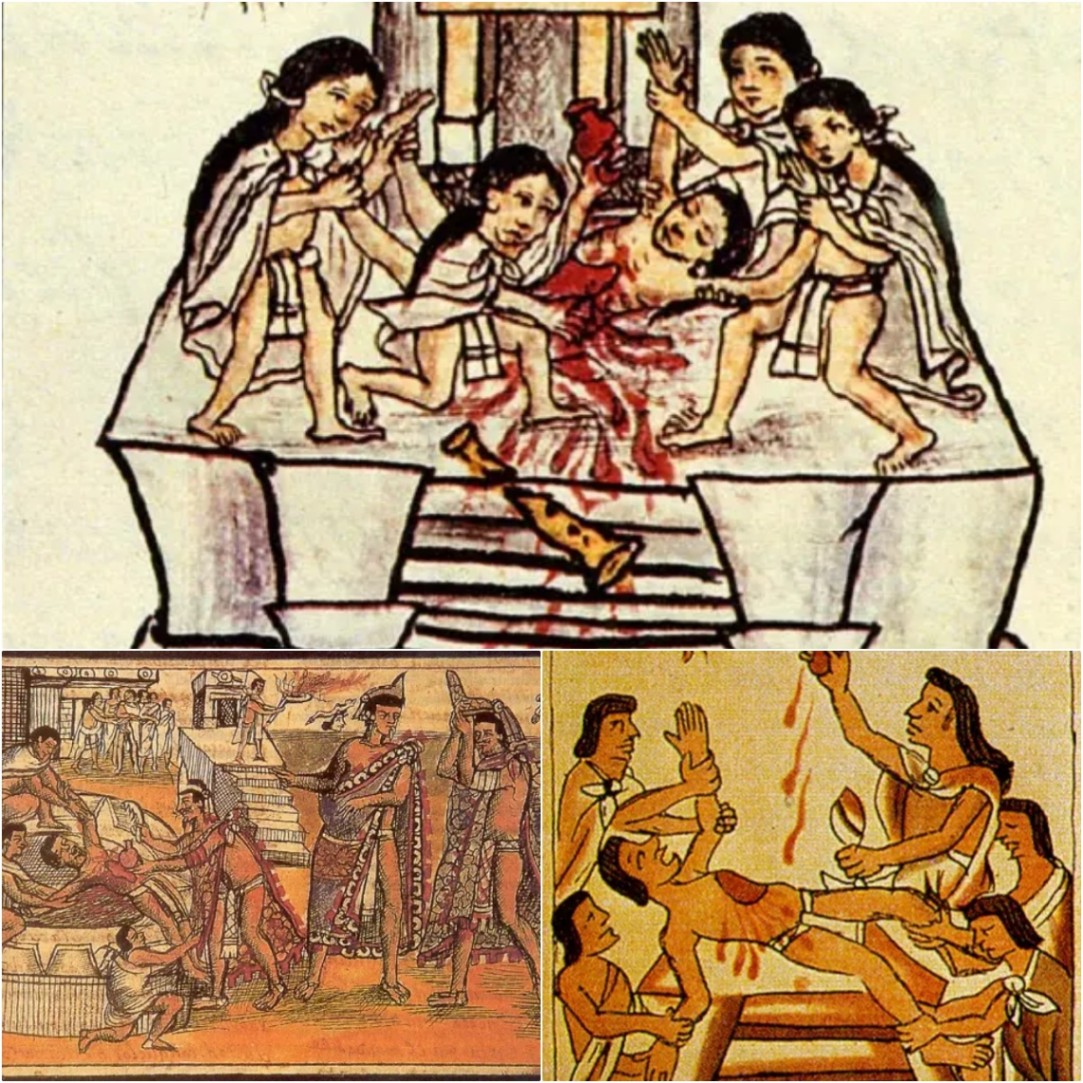

At the heart of Aztec cannibalism lay a profound religious and spiritual worldview, one that saw the consumption of human flesh as a sacred act, essential to the maintenance of the cosmic order. The Aztecs believed that the gods required a steady supply of human blood and hearts to sustain the sun and the very fabric of the universe itself. Failure to provide these sacrifices, they believed, would result in the collapse of the world as they knew it.

The sheer scale of these sacrificial rituals is staggering, with estimates suggesting that tens of thousands of individuals were killed each year in the name of Aztec religious beliefs. The impact of this practice on the conquered peoples of Mesoamerica was devastating, as communities lived in constant fear of being targeted for these macabre ceremonies.

Spanish sources suggest that the majority of Aztec cannibalistic ritual offerings were slaves captured in either battle or as booty from vanquished cities. The majority of these seem to have been men and, of them, largely warriors. Sometimes the most valorous warrior slaves of noble heritage were chosen because of their great fortitude and skill, especially if the sacrifice demanded a difficult, ritualized battle. According to Spanish sources, after the sacrifice was offered to the deity, it was common to first remove the heart, then the head and, sometimes, flay the offering. Once this was done, old men called the Quaquacuilton put poles through the body and carried it back to its owner waiting in the neighborhood’s calpulli house or some other ritual meeting place. The owner could be someone who had bought a slave in the marketplace or the warrior who had captured his offering in battle. Usually, the ritual meal was held in the appropriate meeting house. The sixteenth-century friar, Bernardino de Sahagún, tells us that, in the case of a warrior, the captor’s family could partake of the captive; but not the captor himself. He was considered the captive’s symbolic “father” and it was not proper for him to eat his own.

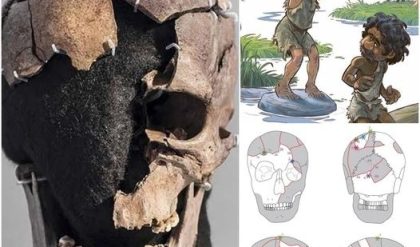

During an excavation in Mexico, archaeologists found human skeletons believed to be evidence that the Aztecs had captured, sacrificed, and cannibalized hundreds of Spanish soldiers when they invaded Aztec lands. The skeletons found in Mexico also showed many holes, pockmarks, injection marks, knife cuts, and tooth marks. Many cooking utensils were also found around the mass graves.

Many believe that the Aztec practice of cannibalism was due to a lack of animal protein in their diet, making human flesh a beneficial food source that they craved. However, in reality, with abundant natural food sources, cannibalism in the Aztec empire was conducted entirely for religious ceremonies and strictly regulated. For instance, enemies captured and eaten ritually were only eaten from the legs or arms, while virgins or children had their hearts and blood consumed.

This cultural understanding of cannibalism as a source of strength and rejuvenation further contributed to the Aztecs’ fearsome reputation, as they were believed to actively hunt and consume their enemies in order to bolster their own power and military might.tb]

The discovery of this gruesome aspect of Aztec culture has undoubtedly left a lasting impact on our collective consciousness. It has forced us to confront the darkest corners of human behavior, challenging our notions of what it means to be “civilized” and questioning the limits of cultural relativism. Although from a modern perspective, the Aztec practice of “cannibalism” is incredibly brutal and savage, to them, it was sacred for both the dead and the living. Those who were sacrificed regarded it as a great honor in their lives.